Summary:

• Scientists have created plastics that break down on their own at programmed speeds.

• The new plastics copy tricks from nature to make them easier to degrade when needed

• This could help reduce plastic pollution and create smarter, more sustainable products.

Plastic waste is a big problem around the world. Most plastics last for hundreds of years and pile up in landfills, oceans, and even natural parks. But what if plastics could be designed to break down after they are no longer needed? That’s exactly what a team of researchers at Rutgers University set out to achieve.

Inspired by Nature’s Polymers: The idea came to chemist Yuwei Gu during a hike, where he noticed plastic bottles littering a beautiful park. He realized that nature makes its own long-chain molecules called polymers—like DNA, proteins, and cellulose—that eventually break down. In contrast, human-made plastics, which are also polymers, tend to stick around for a very long time.

Gu wondered if the secret was in the chemistry. Natural polymers have special groups built into their structure that help them break apart when their job is done. Gu and his team thought: why not use a similar trick for plastics?

How the New Plastics Work: Plastics are made of many repeating units, like beads on a string. The strong chemical bonds between these units make plastics tough and long-lasting. The challenge is to keep plastics strong while they’re being used, but make them easy to break down when they’re thrown away.

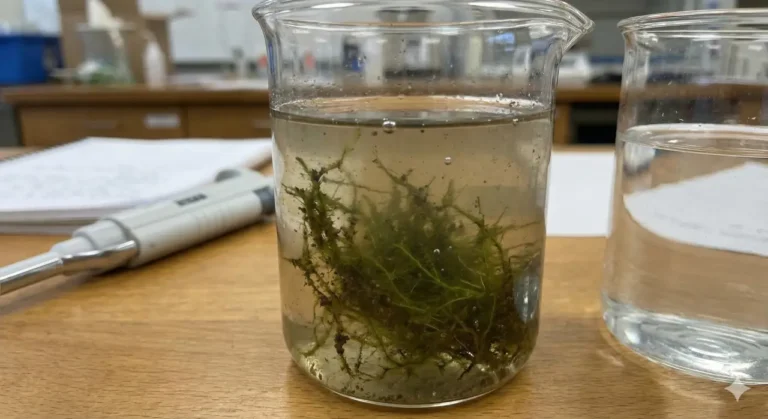

The Rutgers team found a way to build “helper groups” into the plastic’s structure, just like nature does. These groups are placed in just the right spots so that, when triggered, the plastic starts to fall apart—without needing heat or harsh chemicals. The trigger can be something simple, like exposure to air, ultraviolet light, or certain metals.

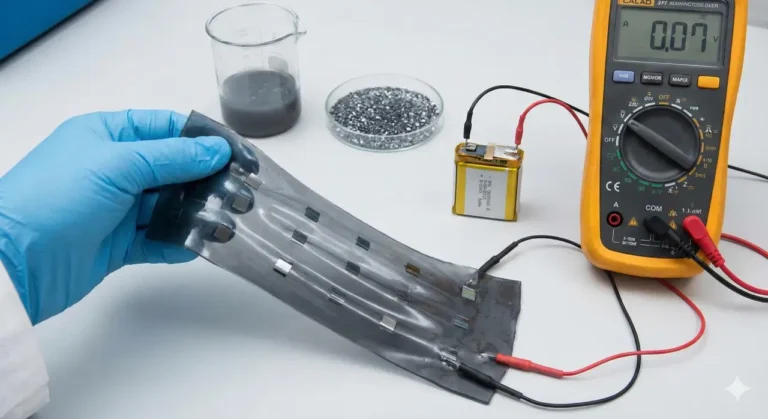

What’s special about this approach is that the speed of breakdown can be programmed. By adjusting how and where these helper groups are placed, scientists can make plastics that last only a few days, or ones that hold up for years. For example, a food container could disappear after a day, while a car bumper could last for years before breaking down.

Why This Matters: If these plastics can be made at a large scale, it could lead to less plastic pollution in the environment. Products could be designed to last just as long as needed, and then safely disappear. The liquid left behind after breakdown is not toxic in early tests, but the researchers are still checking to make sure it’s safe for people and nature.

Beyond packaging and car parts, this technology could be used for things like medicine capsules that release their contents at the right time, or coatings that erase themselves when no longer needed.

What’s Next: The research is still in its early stages. The team is making sure the tiny pieces left after breakdown are safe, and they are working to adapt the process for use with common plastics and current manufacturing methods. There are still technical challenges to solve, but the hope is that, with more development, these self-destructing plastics could become part of everyday life.

This study was published in Nature Chemistry. The research was led by Yuwei Gu (Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences), with contributions from Shaozhen Yin (doctoral student, first author), Lu Wang (Associate Professor), Rui Zhang (doctoral student), N. Sanjeeva Murthy (Research Associate Professor), and Ruihao Zhou (former visiting undergraduate student).