Image for Illustrative Purposes Only.

Summary:

• Marine bacteria play a big role in moving carbon from the ocean surface to deeper waters

• Viruses called phages infect these bacteria, causing them to evolve defenses that can affect how carbon sinks

• Some bacterial mutations make cells “stickier” and more likely to sink, which may help lock away carbon in the deep ocean

The world’s oceans are not just vast bodies of water—they are also home to countless tiny organisms that quietly help regulate our planet’s climate. Among these, marine bacteria play a crucial role in capturing carbon near the ocean’s surface and moving it down to deeper waters. This process helps remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which can slow down climate change.

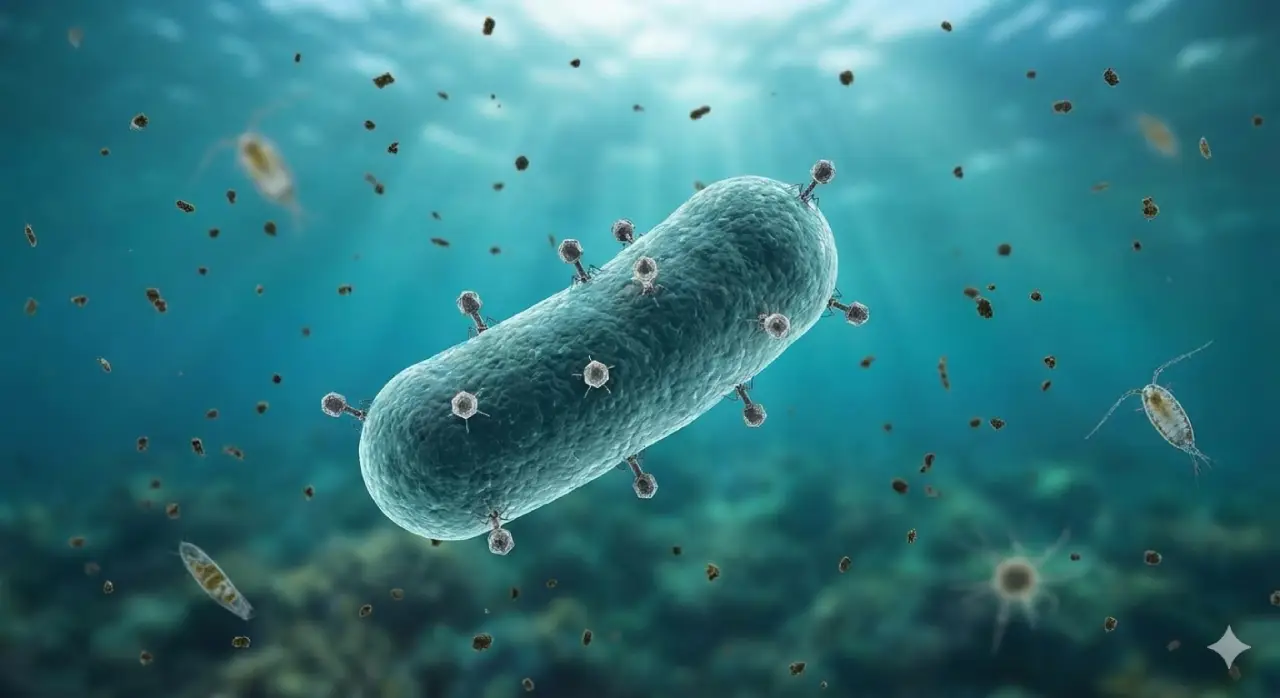

But life for these bacteria is not easy. They are constantly under threat from viruses known as phages. These phages infect the bacteria, forcing them to evolve new defenses to survive. This ongoing battle between bacteria and viruses is like an evolutionary arms race, with each side trying to outsmart the other.

A recent study has shed new light on how this battle affects not just the bacteria, but also the ocean’s ability to store carbon. Researchers found that when bacteria develop resistance to phages, it can change how they interact with their environment—and even how well they help carbon sink to the ocean floor.

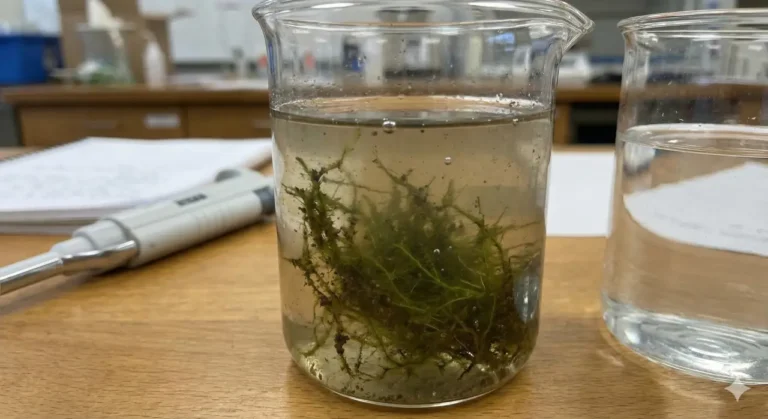

The team studied a common marine bacterium called Cellulophaga baltica and exposed it to different phages. Some bacteria developed mutations on their surfaces that blocked the viruses from getting in. Others had changes inside their cells—called metabolic mutations—that made it harder for the virus to reproduce, even if it got inside.

Interestingly, both types of mutations made the bacteria “stickier.” However, only the surface mutations caused the bacteria to clump together and sink much more easily. This is important because when bacteria sink, they carry carbon with them to the deep ocean, where it can stay for hundreds or even thousands of years. This process, known as the marine biological pump, is a key way the planet locks away carbon and helps control the climate.

The study also found that these mutations come with a cost. The bacteria that were more resistant to viruses tended to grow more slowly. This slower growth could affect other microbes in the community, since bacteria are a major food source and play many roles in the ecosystem.

One surprising discovery was that the internal metabolic mutations changed how the bacteria made certain fats, or lipids, inside their cells. The viruses need these lipids to make new copies of themselves. If the bacteria can’t make the right lipids, the virus can’t complete its life cycle. This finding opens up new questions about how many other hidden ways bacteria might defend themselves against viruses.

Understanding these microscopic battles is more than just scientific curiosity. The way bacteria and viruses interact can influence how much carbon sinks to the deep ocean or is released back into the atmosphere. This, in turn, affects global climate and our everyday lives.

The researchers say there is still much to learn, especially about the less-studied metabolic mutations. As we discover more about these tiny organisms and their complex relationships, we gain a better understanding of how the ocean helps regulate Earth’s climate—and how even the smallest creatures can have a big impact.

This research was published in Nature Microbiology. The study was led by Marion Urvoy (co-first author, The Ohio State University), Cristina Howard-Varona (co-first author, Ohio State), and senior author Matthew Sullivan (Ohio State). Additional co-authors are Carlos Osusu-Ansah, Marie Burris, Natalie Solonenko, and Karna Gowda (Ohio State); Andrew Stai and Robert Hettich (Oak Ridge National Laboratory); John Bouranis and Malak Tfaily (University of Arizona); and Karin Holmfeldt (Linnaeus University, Sweden).